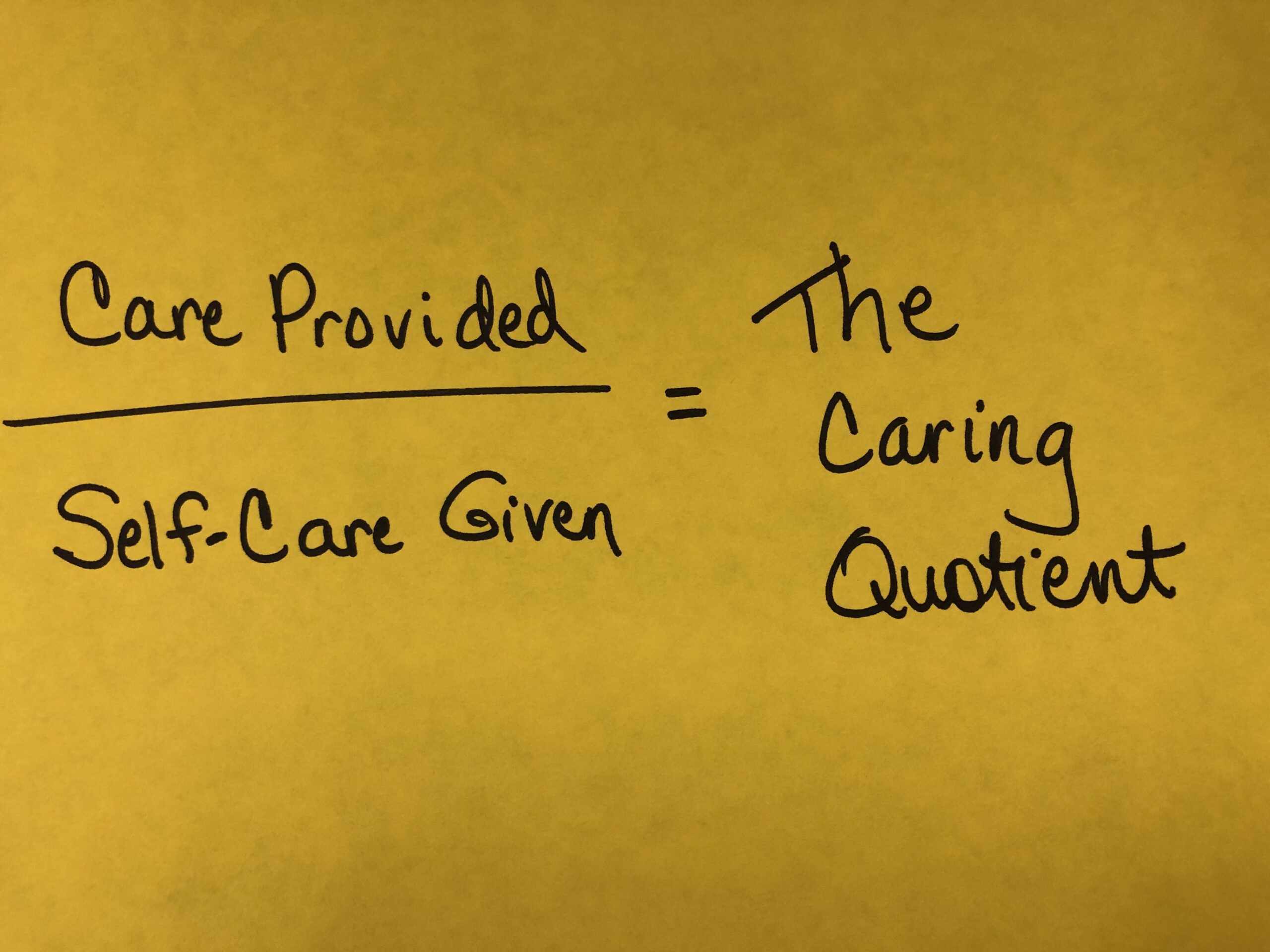

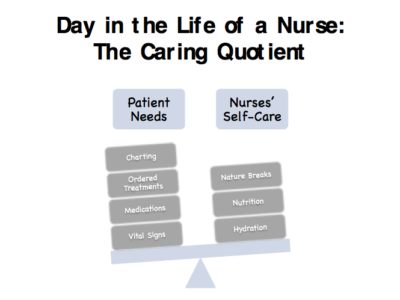

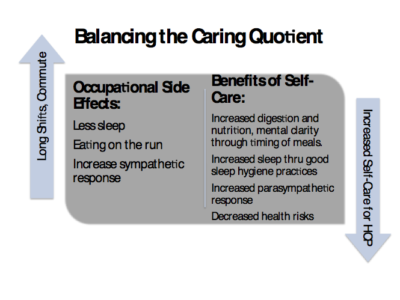

The last couple of months, we have been exploring what I have dubbed, The Caring Quotient, the mathematical equation that shows the relationship between how you serve others while providing for your own self-care. Within this final article in the series, I will describe some of the ways that nurses (and other shift workers) can get The Caring Quotient in their life back into balance.

I hope by now you have had the opportunity to implement some of the steps described to improve your sleep hygiene, as discussed in my last article. As described, starting your day with 15 minutes of sunshine does wonders to turn off melatonin and stop the yawning. Have you started a sleep diary yet or began putting aside all blue-light technology a few hours before going to sleep yet? Tried timers and dimmers on your lights and found it easier to fall asleep?

Whatever you have tried, remember that good quality sleep (usually 7-8 hours for most people) is necessary for long-term health, so if less sleep is experienced over time, there will be consequences. Most nurses can’t do anything about the length of shifts, for it is a part of job requirements. But shift workers can do life hacks, such a skipping a meal or two on the days they work to increase their productivity. What? Productivity could be increased with less food?

I hinted at this phenomenon at the end of my last article as I introduced you, my readers, to a quote from the CDC-NIOSH series that advised to “avoid a high-carbohydrate lunch…to avoid a drop in alertness” during your shift. Why? Since understanding this concept about how different types of eating plans (or timing of eating) might benefit any type of shift worker, we will unwrap this topic together.

You see, our human bodies have an autonomic nervous system that is comprised of two main divisions, the sympathetic nervous system (fight, flight, or freeze), and the parasympathetic nervous system (resting-digesting). So, if you are driving down the freeway munching away at the fast-food you just picked up, that could be problematic. Physiologically, when driving, your brain has to maintain a state of alertness (monitoring the traffic, watching your mirrors, watching the road signs, preparing to change lanes, and evaluating your surroundings of those in other lanes and their approximate distance from you). All of this requires cortisol, the stress hormone, so the brain switches into the sympathetic nervous system mode. But did you know that when the body is in such a state, it slows down the other system (parasympathetic) by shunting blood away from the digestion system while pushing more blood to the vital organs, the brain, heart, lungs and muscles, to enable you to react quickly to any immediate threat or need? Thus, when you are eating while driving and in the sympathetic mode, your body’s digestion system isn’t fully functioning. Result: If you wolf down a meal on the go, physiologically, since your body didn’t withdraw the nutrition from the food, hunger signals would persist.

If my theory about being in the fight or flight mode when driving down the freeway is correct, then most nursing roles are underneath the confines of the sympathetic nervous system during the shift. To care for patients requires the health care provider to be on high alert, prepared to change their course of action at a moment’s notice, if their patient’s condition warrants that. So how can a nurse whose nervous system stays controlled most of the time by the sympathetic nervous system, not only during their shift work, but also on their commutes, facilitate their need for resting and digesting?

Did you know that some nurses are finding that the less they eat and the more they hydrate during their long shifts, the better they feel? How does that work? The concept is called intermittent fasting. For some, they skip breakfast, for others, they skip dinner on the days they work. Either way, they are extending the normal fasting hours (that occurs while we sleep), so even when they can’t get eight hours of sleep between shifts, they can at least give their digestion system and body more than eight hours of going without food. And the less time the body in 24 hours has to digest food, the more rest the body gets. You might remember from sources I referenced within last months article that when someone is sleep deprived, their appetite increases but their metabolism drops.

Some experts believe that the human pancreas goes to sleep about 7pm. If so, does our meals after a long shift have an opportunity to digest? What about late night snacking? Could it be beneficial to limit meals to certain hours to improve the digestibility? Thankfully, research is beginning to uncover some answers.

According to Dr. Jason Fung, a nephrologist, has reported that intermittent fasting has multiple benefits, including increases mental acuity, since the energy normally spent to digest food can be devoted to other endeavors. With his experience utilizing intermittent fasting (12-hours +) with hundreds of diabetic patients, he has become a leading expert in this field. Of course, all of these type of patients with chronic diseases needed to be followed carefully by this clinic, to frequently evaluate lab changes, watching for evidence that the labs were trending toward positive results in their health. But some shift workers are finding that such a bio-hack is also resulting in more sustained energy throughout their shift to care for patients? Hopefully, research in the next few years to come will confirm such benefits.

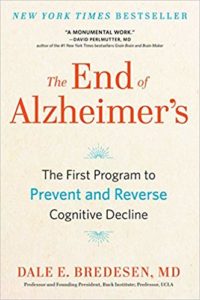

So what exactly is intermittent fasting and how might it help? Basically, it limits the window of time in which you consume foods. So, if you normally have breakfast, lunch, and dinner, then a late snack, dropping the late night snack would extend the break between your last meal one day and your first meal the next day, creating 12-hour intermittent fasting window (6pm-6am, for example). One of my favorite research neurologists has found that without a daily 12-hour break from food, that practice could actually prevent the movement of short-term memories into long-term memory storage in the brain. So forgetting where you laid your car keys the night before might be an example of a short-term memory that didn’t have the opportunity to be cemented into long-term storage overnight. What if years of shift work without enough sleep could contribute to later problems with dementia? According to Dr. Bredsen’s foundational research, the steps toward dementia actually start 20+ years before the first sign is even recognized. If you haven’t read his book, whether challenged with long shifts or other types of chronic stress, I believe you will find his research fascinating and thought-provoking.

So even if you can’t adjust your work schedule or length of your shifts, maybe learning more about nutrition and rest timing, two sides of the same life-hack coin, could help you find a way to perform more optimally. In this time of limited resources and energy in the midst of increased stress, I hope these do-it-yourself options can help you investigate ways to balance the Caring Quotient equation as you focus on this self-care aspect and learn to balance your care for others with caring for yourself!